Earmarks or sheepmarks are patterns cut into the ears of sheep to define and show which farmer owns which sheep. Earmarks have followed animal husbandry ever since the settlement of Iceland. It was necessary to mark your sheep and other animals because the sheep were free roaming and pastures were shared. Earmarks are referenced in old stories and sagas and they are mentioned in ancient lawbooks like „Grágás“ (the Gray Goose Laws) and Jónsbók (John’s book). To mark animals was a kind of art form and many think it is incredible how farmers mark, often very complex earmarks, with old knives. Earmarks were and are often inherited, with many generations sometimes have the same or similar earmarks. A lot of folklore is connected to earmarks and when to cut the ears. This centuries old tradition is still alive and well today.

Marking happens mostly when lambs are very young, only a few days old, using a knife or a clipper to cut specific shapes in both of the ears of the lamb. The aim is always to have the cutting done as quickly and hygienically as possible. There has been a discussion about ending this tradition for certain reasons, but most farmers attach sentimental value to their earmarks, making it an integral part of connecting with one’s animals. Today all the lambs and sheep are tagged with plastic tags that are shot into or pushed through the ear much like an earring, but they are also earmarked. The plastic tags can get stuck in fences, are prone to falling out, and they can also become weathered and unreadable. Earmarks can thus be very useful since they last throughout the animal’s whole life. Earmarking relates not only to ownership, but also to security, such as for disease control and the delimitation of land used for grazing. Still, today it is considered significant to have your own earmark. Earmarks were often given as a gift of opportunity and sometimes a couple living on the same farm have their own personal marks and mark their own sheep. This can become an occasion for funny discussions when they are debating who gets to put their mark on a pretty lamb.

Earmarks, patterns and folklore

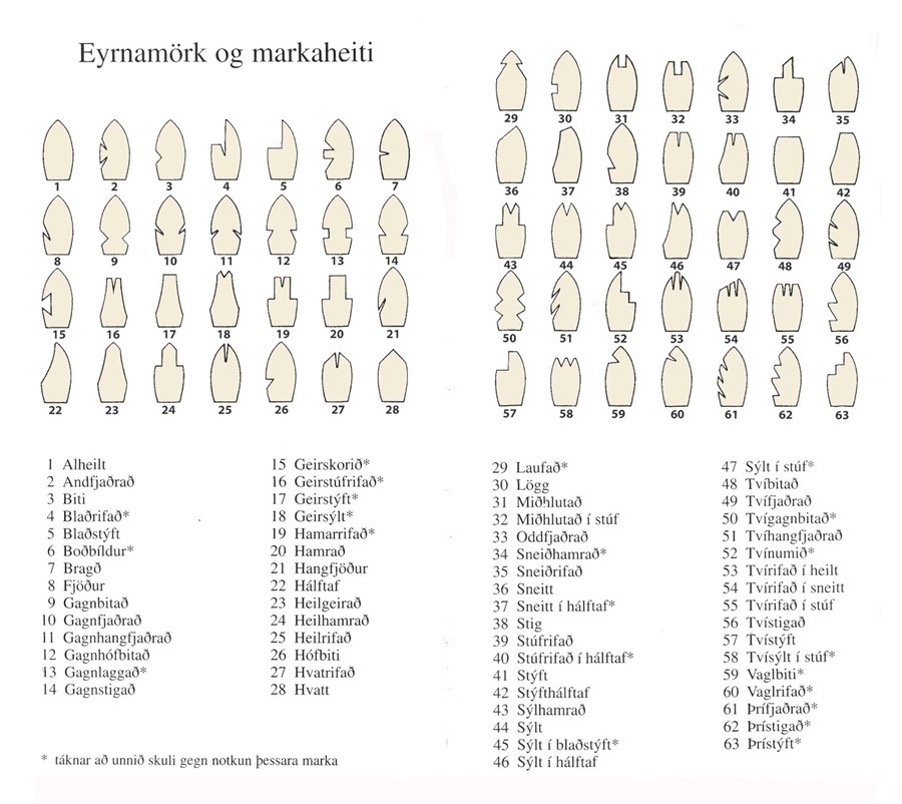

Earmarks or sheep marks are the tradition of cutting specific patterns in the ears of sheep to mark ownership of them. Knives and clippers are mostly used to cut the ears. All farmers (or the farms themselves) have their own specific mark, so nearby farmers that have sheep in the same pastures or lands can identify which ones are theirs. In Iceland there are 63 legally valid earmark patterns, each with their own Icelandic names including:

1) Alheilt 2) Andfjaðrað 3) Biti 4) Blaðrifað* 5) Blaðstýft 6) Boðbíldur* 7) Bragð 8) Fjöður 9) Gagnbitað 10) Gagnfjaðrað 11) Gagnhangfjaðrað 12) Gagnhófbitað 13) Gagnlaggað* 14) Gagnstigað 15) Geirskorið* 16) Geirstúfrifað* 17) Geirstýft* 18) Geirsýlt* 19) Hamarrifað* 20) Hamrað 21) Hangfjöður 22) Hálftaf 23) Heilgeirað 24) Heilhamrað 25) Heilrifað 26) Hófbiti 27) Hvatrifað 28) Hvatt 29) Laufað* 30) Lögg 31) Miðhlutað 32) Miðhlutað í stúf 33) Oddfjaðrað 34) Sneiðhamrað* 35) Sneiðrifað 36) Sneitt 37) Sneitt í hálftaf* 38) Stig 39) Stúfrifað 40) Stúfrifað í hálftaf* 41) Stýft 42) Stýfthálftaf 43) Sýlhamrað 44) Sýlt 45) Sýlt í blaðstýft* 46) Sýlt í hálftaf 47) Sýlt í stúf* 48) Tvíbitað 49) Tvífjaðrað 50) Tvígagnbitað* 51) Tvíhangfjaðrað 52) Tvínumið* 53) Tvírifað í heilt 54) Tvírifað í sneitt 55) Tvírifað í stúf 56) Tvístigað 57) Tvístýft 58) Tvísýlt í stúf* 59) Vaglbiti* 60) Vaglrifað* 61) Þrífjaðrað* 62) Þrístigað* 63) Þrístýft*

(The names that have an asterisk are a bit on the rougher side and their use is not recommended)

Earmarks are divided into overmarks, that cut into the ear tip, and undercuts that cut the sides of the ears. All the undercuts and some overmarks can either be in front (on the top) or behind (on the underside) of the ear.

Earmarks are read in a specific way, they are oriented like you are looking on the back of the sheep’s head, since you would be holding the sheep from behind standing with your feet on either side. So, if a mark is said to be on the right, then it is on the left ear if you look at the sheep from the front. When marks are being read, you start with the overmark of the right ear, then the undermark at the front of the right ear and then the undermark at the back of the ear. The same is then done for the left ear.

Not all earmarks contain the same amount of cuts, for example: Heilhamrað is 4 cuts, tvístýft 3 and Stýft is only 1.

Rough earmarks were often called „dirty marks“ but dirty marks were also marks that were unreadable or badly cut. Rough marks were also called „blood marks“ or „wounding marks“. Easily readable marks are called „obvious marks “, and they are readable from a distance, so you don’t have to catch the sheep to know who owns it. Not all marks were equally prosperous and there are documented cases of people that have changed their marks to become luckier in animal husbandry. It was also said that if a lamb is born with the ears already marked (with a mark that was not in use) then the farmers should adopt that mark and use it because it was a lucky mark. After cutting the ears it was possible to pinch the cut to stop the bleeding, but in former times some farmers put dry dirt on it to stop the bleeding.

In some places lambs weren’t marked while the tide was high because it was (and in some places still believed) that lambs bleed more during high tide than low tide.

Lambs that were given to children often got a ribbon through the ear in the past, which was done by threading the ribbon in a needle, then dragging it through the ear before knotting it on both sides so it wouldn’t fall out. This was called „ornate dragging “ in some places.

It was also said that if you ate a marked sheep’s ear that you would then become a sheep thief or that your sheep would get stolen.

From the settlement of Iceland to the modern day

Marking sheep has great historical value in Iceland and has since antiquity because the mark carried the proof of ownership of the animals, which were the farmer’s most valuable possessions. In ancient stories, marks on farm animals are sometimes mentioned and the law of that time explains them clearly. The Gray Goose Law states that all farm animals should be marked; every sheep, cow, pig and goat except for the animals walking with their mothers on the farmstead. In those laws its stated that these animals should be marked on the ears and not any other place. Horses were exempt from this law, perhaps because it would lower the value of the horse or harm the close relationship held between the horse and the farmer.

Earmarks clearly came to Iceland with the Norse settlers. They were present in all the Nordic countries and are still in use in the Faroe Islands, Norway and the Shetland Islands. The marks that these countries use aren’t only made in the same patterns as the Icelandic ones, but have the same or similar names. Gagnbitað in Iceland is called „Gangbit“ and Fjöður is „Fidder“ in the Shetland Islands.

The Faroese have no marks that are not found in Iceland, but they don’t have a lot of the rougher marks that Iceland has.

Owning a mark indicated a certain status in the farming community. A mark became a part of the local history. In herding and réttir, a pen that the sheep are kept in and then sorted out to the farmers that own them, earmarks and knowledge of them has always been critically important. Earmark-Leifi from the Skagafjörður area was famous for knowing every mark and who owned them. The oldest earmark register (a list of marks and the names of their respective owners) were handwritten in the beginning of the 19th century and then in 1855 the first registers were printed.

Women owned earmarks just like men. Farmers wives often owned their own marks, but if the woman didn’t own a mark and became a widow then she usually continued to use the mark of her late husband and would register it as her own.

Kristján Magnússon a farmer and a district governor at Skógarhollt in Þingvallasveit, who was born in 1778, owned the mark „sýlt, biti behind right“ and „sýlt, biti behind left“. The mark was recorded in the 1830, 1835 and 1840 earmark registers. He had 8 children with the farmhand Guðrún Þorkelsdóttir between 1816-1839 after having had 7 children with his actual wife. Kristján confessed his love for Guðrún in many ways, one of which was gifting her an earmark as proof of loyalty. The mark was almost the same as the one he owned and used, her mark was ,,sýlt, biti in front right“ og „sýlt, biti front left“. This mark is first recorded as owned by Guðrún in the 1830 mark register when she lived on the farm Brúsastaðir in Þingvallasveit where the government put her so she and Kristján wouldn’t commit more adultery. In the year 1837 Sigríður, Kristján’s actual wife, dies, and after that no one could ban him and Guðrún from living together. She is recorded in the 1840 earmark register as living on the same farm as him. After Kristjan’s death in 1843 Guðrún moves in with her daughter Salvör that lived at the farm Fellsenda where her mark was then registered in the 1850 and 1855 mark register.

The marks of the bishoprics seem to have been pretty rough, for example „Sýlt í stúf in both“ was the mark of the Skálholt bishopric in the 18th century. The story goes that before that mark they had another called „afeyrt both“, which was just both ears cut off. It was a dirty mark or a „thief mark” because you could just cut the ear of a sheep and claim it. This mark was also at one point said to have been the mark of the Danish king. The devil also had his own mark according to the folklore which was: “Þrírifað í Þrístýft and thirteen rifur into Hvatt.”

Earmarks have also ended up in poetry. In an old folk tale the mark of a mountain dweller is explained with this Icelandic poem:

Mórauður, með mikinn lagð,

mænir yfir sauðakrans;

hófur, netnál, biti, bragð

báðum eyrum mark er hans.

Earmark registers existed on every farm and still do. Every farm had its own mark, one or more. It was very important to people that their mark was kept within the family. The ones who knew all the marks didn’t need mark registers and most farmers knew what mark the farms around them owned. It was very respectable to know all the marks and their owners. The people that did not know the main marks were not seen as good farmers. Old marks were frequently fixed and simplified, especially if they were complex. They were never changed too much; the core of the mark, the overmark, was preserved. It was also very important that the mark wasn’t too rough, cut the ear too much. This way complex and difficult marks became simpler and cleaner with the years and new generations. People also felt it was good to own several marks and they were often different versions of the same core. Those extra marks were often put on special sheep, ones that are considered fertile, have 2 or 3 lambs or lambs that are born from a line of especially good sheep.

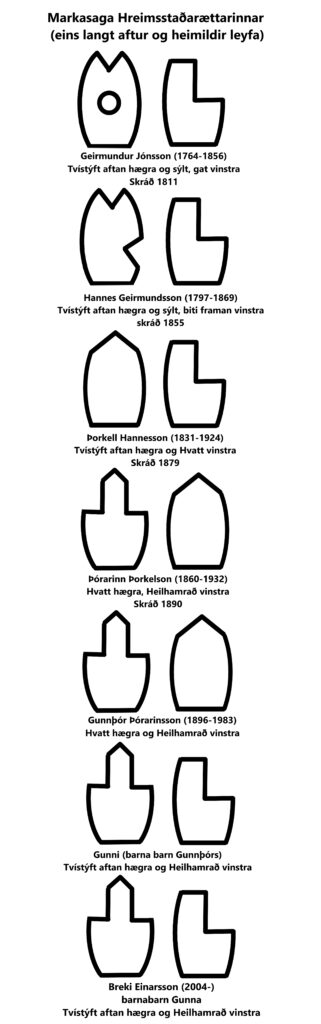

Marks were often inherited. It was an heirloom, not just as a useful tool but as a family legacy. It is very likely that earmarks, which have been inherited from farmer to farmer for generations, are the oldest Icelandic heirlooms. The marks followed the family through the centuries in the old farming community. Many people have kept their ancestor’s legacy alive by keeping their marks, even if they themselves don’t own any sheep or other livestock. Marks that were used on a specific land for a long time became part of that land’s image outward. People could not imagine the mark not being a part of the family. Sheep farming was and is the basis of farming in most regions of the country, and the mark was a kind of characteristic symbol of the farm.

Arnór Karlsson, a long time farmer at Ból and the markwarden in Árnessýsla, says in the Árnessýsla mark register from 1996: „many love their marks and think of them as heirlooms.“ Furthermore in the 2004 mark register Arnór says: „most of the markowners are sheepowners but many others want to own marks. Those people are both farmers that have retired and others that, may never have owned sheep, but want to keep the marks of their forefathers alive and in the family. A rich and lively tradition seems to be connected to the marks as heirlooms and “my grandfather’s mark” has a special meaning in the hearts of many.” It was common that old farmers gave their mark either to their favorite descendant, the one that was inheriting the farm, or just to the one that wanted it the most. Arnór also adds that in a recorded dispute there were two men that had the same mark in the same area, both claiming ownership over the mark. Afterall, it was stated that the mark had been registered to one of the men’s ancestors in the mark register of western Árnessýsla in 1825 and the mark was therefore awarded to him.

According to the 2017 register from the Farmers’ Associations there were about 17,000 earmarks registered in the country.

From farmer to farmer

This tradition has remained mostly unchanged throughout the centuries. The same marks are used and there are mark registers for all legally registered marks for every area in the country. There are 26 areas based mostly on the old county system in Iceland. Like in the olden days, no two people can have the same earmark in the same area. There are mark wardens for every area and they oversee the registration of marks in the national register and make sure every mark is different. The mark registers are published all around the country every 8 years, showing all the valid and legally registered marks and their owner’s names.

Even though the use of earmarks has decreased somewhat, being replaced by plastic tags in some places, the tradition is nowhere near extinction. Many own marks but no sheep, while others mark their sheep instead of using the plastic tags, and many others use both the tags and their marks. Many farmers have adopted different traditions relating to earmarks and when sheep are marked. Farmers can, for example, have strong thoughts on when the best time to mark a sheep is, how old the lambs should be, and how to mark. This is mostly related to decades of experience and what they have learned from older generations.

Most people that own sheep participate in this tradition and many of the decendants of farmers and/or farmers that have retired, own their own marks. Essentially, most people that are involved with Icelandic sheep farming participate in this tradition. Marks are often the subject of the Farmers’ Association, but „Landsmarkaskrá“ or the National Mark Register keeps track of all marks and serves as the headquarters of the tradition to a certain extent.

As stated before, there are still a lot of farmers that own and use earmarks, and most of the time those earmarks have a long and complex history. This story goes from farmer to farmer and the more complex the story is the more likely it is to get passed down and remain in use by the family.

Further information on earmarks/sheepmarks:

Spurningaskrá um fráfærur hjá Þjóðháttasafni Þjóðminjasafni Íslands, þar er meðal annars spurt um mörkun lamba:

https://sarpur.is/Spurningaskra.aspx?ID=531257

Sagnaþættir Guðfinnu eftir Guðfinnu S. Ragnarsdóttur. Gefin út af Forlaginu árið 2017.

Svar um mörkun búfjár frá Vísindavefnum:

https://www.visindavefur.is/svar.php?id=6598

Landmarkaskrá:

https://www.landsmarkaskra.is/index.jsp

Mörk og merkingar búfjár e. Halldór Guðmundsson:

https://www.bbl.is/skodun/lesendaryni/um-mork-og-merkingar-bufjar

Skráning eyrnamarka og útgáfa markaskráa e. Ólaf R. Dýrmundsson og Guðlaugu Eyþórsdóttur:

https://www.bbl.is/skodun/a-faglegum-notum/skraning-eyrnamarka-og-utgafa-markaskraa

Landsbókasafnið varðveitir eintök af flestum markaskrám, alveg frá upphafi.

Myndasafn

If you look at the ears you can see the pattern of the cut. Here the cut is: Alheilt (whole) on the right and hamrað on the left. Photo: Dórótheu Sigríður.

Here the earmarkings are: "Sýlt" on the right ear og "sýlt" on the left ear. Photo: Árni Davíð Haraldsson.

Even from a distance you can sometimes read the marking on the ears. This ram has the pattern: sýlt, biti (part) on the front right ear (the part is not clear on the picture) and blaðstýft back of the left ear. Photo: Gróa Jóhannsdóttir

The marking is read: "Sneitt aftan (at the back), hófbiti framan (at the front) and alheilt (whole). Photo: Sigurlaug Dagsdóttir.

The pattern here is: "Sýlt and stig aftan" on the right ear og "tvístíft framan" on the left. Photo: Dóratheu Sigríður.

The earmark is: "Sýlt and stig" on the back of the right ear and "tvístíft" on the front on the left ear. Photo: Dórathea Sigríður.