In Iceland, methods and traditions for catching, processing and consuming hardfish and stockfish can be traced back to the skills and food traditions of the settlers. Despite enormous changes in food processing methods and consumption, fish is still air-dried in Iceland, either outdoors or indoors, and consumed in the same way as Icelanders did centuries ago, without cooking and often with butter on top. The tradition is practiced throughout the country. Fishing and processing is restricted to communities on the coast, but dried fish consumption is independent of residence and common among those who have grown up with this food tradition.

Skráð:

31.01.2025

Skráð af:

Slow Food Reykjavík

Skráð af:

Guðmundur Guðmundsson

Landfræðileg útbreiðsla:

Allt landiðA Living Tradition with Ancient Roots: From outdoor to cabinet drying

In Iceland, methods and customs for catching, processing and consuming hardfish and stockfish, extend back to the skills and food traditions of the settlers, and from there back to Norway.

The tradition in question is multifaceted. It consists of catching and processing methods, which once aimed at procuring a durable food product, that could be stored to ward off the threat of famine. Today, the aim is to produce a food product that has a special taste and texture and is a pleasant addition in today’s consumers’ society.

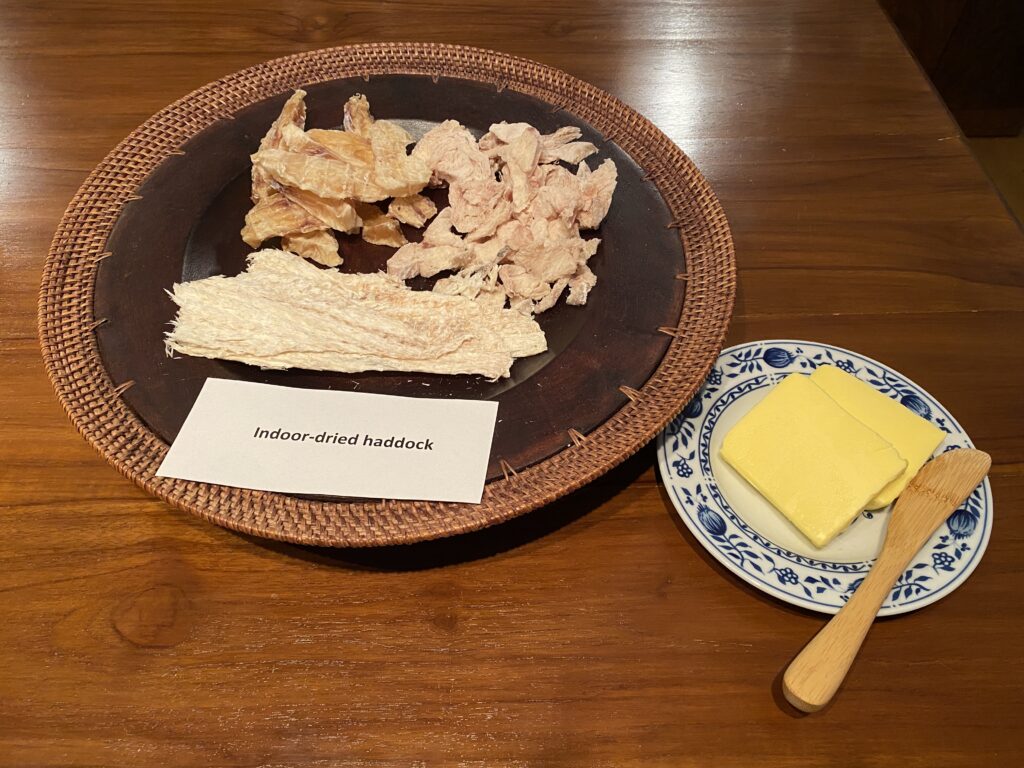

The tradition also consists of eating habits that were initially shaped by the lack of firewood. Instead of soaking the fish, it was beaten to soften it and then eaten with sour butter or other fat. Despite the advent of many household appliances and diverse cooking, the consumption of hardfish has changed surprisingly little. The fish is no longer beaten, but rather passed through a machine that softens it, but it is still eaten dry and often with butter, which is actually salted and not sour as before.

The role and importance of hardfish in the Icelandic diet is very different from what it used to be. Instead of being a staple food, it has become a convenient snack. Furthermore, due to its high protein content, many people consider hardfish a health product.

Finally, it should be mentioned that dried fish is intertwined with the Icelandic language. This is reflected in proverbs, poetry, mantras and folk tales. Although much, of what was common in the language of the ancestors, has disappeared, many people still know a humorous poem that begins like this: “May I have hardfish, yes hardfish with butter”, and even today a violent fellow might threaten someone with the words “I will beat you like hardfish if…”.

Processing of stockfish has undergone various changes over time. In the old days, when the raw material was split before drying, the words skreid and hardfish were synonyms for stockfish. In the 20th century, when Icelanders stopped splitting the fish they dried for export, and instead hung from racks, gutted and headed roundfish, the word skreid became to be used for dried roundfish for export. The afore mentioned change in processing did not apply to dry fish that was consumed domestically. For this market, the fresh fish continued to be split or filleted before drying. Then the word hardfish became to be used for the domestic product. This difference in wording is still in use.

Outdoor drying is only practiced between September and May when the temperature is low and the maggots are dormant. Drying racks and sheds are usually located at the coast where the wind blows. When drying outdoors, it is of utmost importance to pay close attention to the weather, such as rainfall and temperature. Fluctuating weather conditions can cause problems during drying. Many processors prefer the fish is hung in frost, but if snow covers the fish before it dries, it may spoil instead of turning dry.

In the last decades, indoor drying has been taken up on a large scale. Today, much more fish is dried indoor, in drying chambers, than outdoors. Indoor drying has many technical advantages over outdoor drying. The drying time is shortened from 4-6 weeks to a few days, and main parameters are under control: temperature, air speed and humidity. Since the cabinets are closed, maggots cannot enter, and the fish can therefore be processed all year round. A drawback of indoor-dried fish is that the product tends to have less flavor than outdoor-dried fish. To compensate for this, more salt is frequently used when fish is dried indoors.

Each processor has developed his own version of outdoor and indoor drying. Today, the fish is always filleted and rinsed of bones before drying. Outdoor-dried fish has skin on, while indoor-dried fish can be with or without skin. For indoor drying, the fish is often cut into pieces. A popular version is based on freezing fish fillets and then cutting them into pieces before finally drying. The result is a sort of cripsy and crunchy snack.

Fish heads and bones, and even fillets, can be dried indoors, but headed roundfish is not dried indoors in Iceland. In the second half of the 20th century, dried roundfish was exported to Italy and Africa, but very little roundfish has been processed in recent years. Cod heads and backbones, on the other hand, have been dried on a large scale both indoors and outdoors, and the products exported to Nigeria. When drying roundfish outdoors, special care must be taken to ensure that the fish does not freeze.

Hardfish fish is consumed all year round, but is probably more common in the summer than at other times of the year. It is a popular snack on hikes and when traveling, all year round, both in Iceland and abroad. Hardfishis popular with those who care about their health. It is always a part of the menu at the traditional mid-winter festivals.

Tremendous progress has been made in boat-making and fishing equipment from the days of settlement, but nevertheless, fish that is caught by handline or longline, is still the best raw material for hardfish.

The introduction of indoor-drying approximately forty years ago has brought great changes to the processing of hardfish and stockfish. Today, indoor-dried hardfish has a much larger share of the market than the outdoor-dried product. At the same time, the drying of cod heads and backbones has largely moved from outdoor-drying to drying in cabinets.

The importance of hardfish in everyday diet has decreased greatly from what it was for centuries. It is no longer a stable food, frequently eaten at every meal. Instead it has become a snack, that is consumed irregularily and between meals. Despite this, the culinary habits are similar to what they have always been. The introduction of electrical appliances and cooking devices has not changed the culinary traditions. Like in the old days, hardfish is consumed dry and uncooked, and frequently with butter.

Traditions related to hardfish consumption have moved between generations. Children learn the traditions from their parents, which in turn learned them from their parents. Traditions related to hardfish are part of the everyday live of people throughout Iceland, although fishing and processing are solely in the hands of fishermen and processors.

„The Fish-Eaters´ Island“

Iceland was settled by Norwegians in the 9th century, and archaeological remains indicate that the country was already a fishing outpost before final settlement in late 9th century. Archaeological research also shows that soon after arrival the settlers began fishing.

Of the numerous species of fish found in Icelandic waters, cod has always been most important, and its migrations around the country have greatly influenced the way fishing is done. The very name of the fish, „thorskur“, means dried fish. Drying fish outdoors has been known in Norway since time immemorial, and the settlers undoubtedly knew the method. It is therefore likely that soon after arrival, the settlers began drying that part of the catch that was to be stored. Accordingly, dried fish is as old as the settlement of Iceland.

At the time of settlement, it is estimated that 20-30% of the country was covered in birch woodland, but as soon as people arrived, they started extensive deforestation. The settlers needed pasture land and firewood, building materials and wood for charcoal production and metal-working. Over time, the woodlands declined greately, and after 1100 years of settlement, birch forest covered only about 1% of the land.

Lack of firewood and the cold climate shaped the food tradition of Icelanders. Icelanders first and foremost consumed milk foods, meat products and fish. Since salt was not available, other preservation methods had to be sought; drying, fermenting and pickling. Fish was dried or fermented, meat was dried by smoking, or pickled in sour whey, along with meat offal and various other foods. All these foods were eaten cold.

Preservation by air-drying had benefits in the old society. Hardfish kept very well, it was lightweight and since it was eaten uncooked, no firewood was needed for cooking. Foreigners were astonished how much fish the Icelanders ate, and how they consumed it. Instead of soaking the fish in water, they softened it by beating, and then ate it uncooked with butter, like bread. In reproach, they called Iceland the „fish-eaters‘ island“. Icelandic scholars protested these insults, but they were not unfounded.

Historical sources indicate that in Iceland it was common to eat hardfish with butter or other fat with each meal of the day. It was not until the 19th century that this practice changed with the importation of cereals and other foods, as well as the widespread cultivation of potatoes.

Major and inevitable changes followed when Iceland’s isolation was interrupted at the end of the 19th century. Furthermore, with modernisation and increased wealth in the 20th century, the diet of the population changed dramatically. It is quite remarkable that hardfish kept its place through this complete overturning of Icelandic society, and it is still a very popular product with a large segment of the nation. Despite all the technical capacity of modern kitchens, the fish is still eaten in a similar way as the ancestors of modern Icelanders did for centuries. It is softened and then consumed dry. Frequently butter is on top. Instead of eating hardfish with meals as bread, it is today eaten between meals as a snack.

Hardfish Is Still Popular

Hardfish is still very popular in Iceland and is available in almost any grocery store and gas station, but the indoor-dried product has a much larger marketshare than the outdoor-dried hardfish. A large part of the production is sold during the summer in connection with travel and outdoor activities, but hardfish is not a seasonal products. It is consumed all year round.

Hardfish in homes and restaurants: Despite the technological advancement of modern kitchens, hardfish is eaten uncooked and without other preparation, and often with butter. In homes, hardfish is usually eaten between meals, – as a snack.

In restaurants, hardfish is commonly served in the traditional way, in suitable pieces with butter, but still some chefs use hardfish and stockfish as a sort of spice in complex dishes, and hardfish and stockfish have their place in the new-Nordic kitchen. The restaurant Dill, the first in Iceland to get a Michelin star, uses both stockfish and hardfish in food preparation.

It can also be mentioned that in 2018, a recipe for a hardfish soup won a competion organised by Iceland‘s Culinary Treasures, a governmental initiative. The idea was to update national dishes and utilize in a new way. Students from the Hotel and Food School adapted recipes that took part in the competition.

Hardfish while traveling: During traveling around Iceland, it is popular to bring hardfish along as a snack. It stays well, is light and nutritious and a very popular snack for hikers, both summer and winter. Even when Icelanders travel abroad, they are tempted to pack hardfish.

Hardfish during mid-winter festivals: Hardfish is an indispensable part of the food offered during the month of Thorri, both on the mid-winter festivals and in homes. The festivals are very popular, and there a large part of adult Icelanders consume hardfish. In the month of Thorri, the fish is usually served in appropriate pieces and with butter.

Hardfish as a health food: Hardfish fits well with the health awakening that today is popular in the West. Marketing of hardfish is often directed at athletes and fitness enthusiasts. The very high content of protein and healthy fatty acids appeals to those looking for foods with health benefits. Hardfish can also be used in special diets, such as low-carb diets.

Hardfish for tourists: In order to introduce Icelandic food traditions to tourists, numerous restaurants offer a taste of hardfish, sometimes with fermented shark and a shot of aquavit.

References:

Arnór Snorrason, Björn Traustason, Bjarki Þór Kjartansson, Lárus Heiðarsson, Rúnar Ísleifsson, Ólafur Eggertsson (2016). Náttúrulegt birki á Íslandi – Ný úttekt á útbreiðslu þess og ástandi. Náttúrufræðingurinn 86(3-4), 97-111.

Ásbjörn Jónsson, Guðrún Anna Finnbogadóttir, Guðjón Þorkelsson, Hannes Magnússon, Ólafur Reykdal, Sigurjón Arason (01 May 2007). Harðfiskur sem heilsufæði. Matís. https://matis.is/skyrsla/hardfiskur-sem-heilsufaedi/.

Gísli Gunnarsson (2004). Fiskurinn sem munkunum þótti bestur. Ritsafn sagnfræðistofnunar 38, Háskólaútgáfan.

Gudmundur Jonsson (1998). Changes in food consumption in Iceland, 1770–1940. Scandinavian Economic History Review 46(1), 24-41.

Hallgerður Gísladóttir (1999). Íslensk matarhefð. Mál og menning.

Jón Þ. Þór (2002-2005). Saga sjávarútvegs á Íslandi I-III. Bókaútgáfan Hólar.

Lúðvík Kristjánsson (1980-1986). Íslenzkir sjávarhættir I-V. Menningarsjóður.

Matís (ódagsett): Þurrkun. https://alltummat.is/vinnsluadferdir-matvaela/thurrkun/

Oddur Einarsson (1971). Íslandslýsing (Sveinn Pálsson þýddi). Menningarsjóður.

Páll Gunnar Pálsson (07 Feb 2014). Þurrkhandbókin – fjölbreyttar og gagnlegar upplýsingar um þurrkun á fiski. Matís. https://matis.is/handbaekur/thurrkhandbokin/

Myndasafn

Stockfish hung from racks in Akranes. Approximately 500.000 fish are being dried. Photo taken in 1953. Source: Haraldur Sturlaugsson.

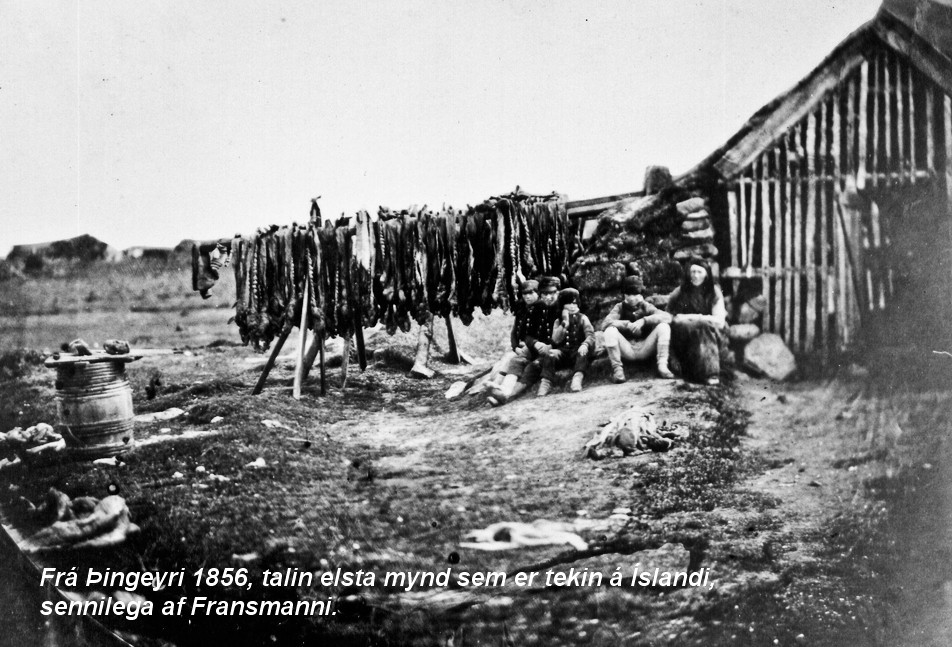

A man standing in front of a rack with dried wolffish. Photo taken in Thingeyri in the year 1856. Source: The Blue Bank in Thingeyri.