I’m bored of lying here in an ugly cave;

it’s better at home in Helgafell

where they have dancing and wrestling.

Glíma has been a part of the life of Icelanders from the original settlement of the land until today, and it evolved in parallel with the multitude of changes that Icelandic society has undergone. Based on the folkloric poem above, spoken by a dead man in his grave, glíma even followed Icelanders between one world and the next.

Skráð:

29.09.2021

Skráð af:

Glímusamband Íslands

Skráð af:

Reynir A. Óskarson

Landfræðileg útbreiðsla:

Allt landiðFor the most part, glíma has an unbroken history from Iceland’s earliest days through to the present day. From the original settlement of the land to the loss of independence to the changes of ruling kingdom; through natural disasters, pandemics and mass emigrations; from heathenism to the conversion to the reformation; through all these changes, glíma has stood by the side of Icelanders and refused to move an inch when the situation turned hard, much like a loyal dog.

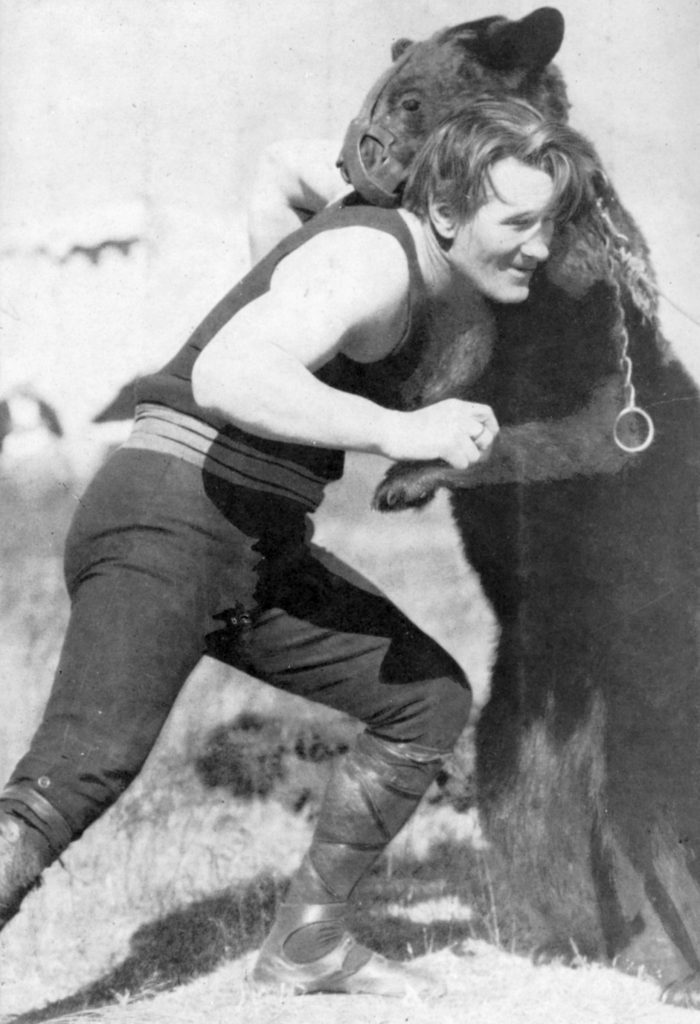

In reality glíma is the only sport that survived the Viking Age. Glíma was to Icelanders a tool of survival in the days when the very real threat of a violence lay around each corner. Later, glíma became a pedagogical tool for training youth when the violence of the earlier era diminished. Glíma was one of the most powerful weapons in the battle for Iceland’s independence as Icelanders began that struggle. And in the recent decades, glíma has been a noble, as well as an unconventional sport for the public to participate in.

The purpose of glíma has changed through the ages, and accordingly, the methodology for glíma has changed as well. All these changes can be followed, because glíma has a nearly unbroken history from the beginning of Iceland’s settlement. The glíma of old was like a Swiss-army knife: one tool with many purposes. Glíma was an activity of entertainment wherever people congregated. Glíma was one of the surest ways to prove oneself and one’s worth to others. Glíma was a practical method for keeping oneself warm during winter travels in the frigid Icelandic climate. Glíma was a brutal weapon and tool of survival in a dangerous world.

Glíma was used to take down giants, ghosts, zombies, outlaws, armed enemies and many other evil-doers. Even empires were taken down a notch using glíma during Iceland’s march to independence.

A grand turning point in the life of Icelanders as well as in glíma occurred when the monumental idea of national independence sprang into the national consciousness during the middle of the 19th century. It was a period of great turmoil, when Icelanders had to make decisions about what it was to be Icelandic: what elements were Icelandic, and what elements were not Icelandic. Glíma became a tool for separation and distinctiveness. Glíma became something that could be called uniquely Icelandic: the sword and the shield of a new nation.

It was then that we see for the first time the glíma we know today: the modernized glíma. This new and spectacular future of glíma seems to have originated at the school at Bessastaðir, which was the center of education in Iceland at this time. Students practiced glíma each day in the lobby of the Bessastaðir school. These students later were the people who most enthusiastically agitated for and guided the move to Icelandic independence. Today Bessastaðir is the official residence of the president of Iceland.

Only recently has it become clear the degree to which these changes in glíma during this period empowered Icelanders.

When Iceland declared independence on June 17, 1944, glíma was practiced both in Iceland and abroad, wherever Icelanders celebrated their independence. Glíma had been a catalyst for Iceland becoming a free and independent nation.

After independence, glíma continued to evolve. Its purpose changed again, since it was not needed as a tool of separation and uniqueness to the same degree.

Today, glíma is an organized sport with its own union inside the national Olympic and sports association of Iceland, just like other sports. Men and women of all ages participate and compete in glíma using a formal set of rules, and with formal training available.

Glíma will always be more than merely a competitive sport. Glíma has stood next to Icelanders from settlement through today, maintaining Iceland’s ancient legacy. Despite the changes through the centuries, the spirit of the settlement-era glíma still holds strong in modern glíma. Many of the throws are the same and bear the same names as in the ancient sources. The modern glíma-belt encourages a very similar methodology of delivering the throws as is depicted in the ancient sources. A clear example is the hábrögð (high tricks) where one’s partner is raised to the chest of the thrower and then thrown down.

Ancient glíma is in evidence in the placenames of multiple locations around Iceland: Fangbrekka (wrestling hills) in Þingvellir, Glímustofu (Glíma-hall) in Dritvík; and Hryggbrjóti (back-breaker) in Hringsdalur. Throughout the world, Hryggbrjótur remains the only known glíma-stone, used in ancient times to break the back of one’s opponent.

Echoes of glíma remain as phrases in the everyday speech of Icelanders, with sayings such as: að ná undirtökunum (to have the undergrip in wrestling, which means to have the upper hand in a dispute); að láta kné fylgja kviði (to let the knee follow the lower abdomen, a controlling position on the ground, which means to follow through fully); and many others.

Today glíma is more than a tool of survival, more than a pedagogical tool, more than a tool of separation and uniqueness, more than a sport, and more than a method of wrestling. Glíma is the culture, history, and mentality of Icelanders in a moving art form. Glíma rightly holds the title of the National Sport of Iceland.

Sources

A list of the sources used to write this article is too long to add in here. Thus, we provide only a summary instead.

Sagas of Icelanders such as Grettis saga

Legendary sagas such as,

Kings’ sagas such as Magnússona saga

Folklore collections such as the Saga of Guðrún glímna in the folklore collection of Jón Árnason, Þjóðsögur

Manuscripts stored in the National Library’s archives such as Lbs 2413

Travel journals and descriptions of Iceland such as Ferðabók Eggerts Ólafssonar og Bjarna Pálssonar um ferðir þeirra á Íslandi árin 1752-1757

Memoirs such as Minningar glímukappans by Stefán Jónsson

Other glíma related writing such as Glímur by Hermann Jónasson

Websites

Website of Glímusambands Íslands https://glima.is/

Myndasafn

The belt of Grettir and the necklace of Freyja are the two trophies that Glíma competitors strive to attain. Those who attain it are given the title of Glíma king and Glíma queen of Iceland. The belt of Grettir is the oldest trophy in Iceland.

An intense moment in the women’s division match between Marín LaufeyDavíðsdóttir and MargrétRúnRúnarsdóttir. Glíma touches upon most aspects of Icelandic society, and the rights of women is no exception. It wasn’t until 1988 that women attained the right to compete in glíma.

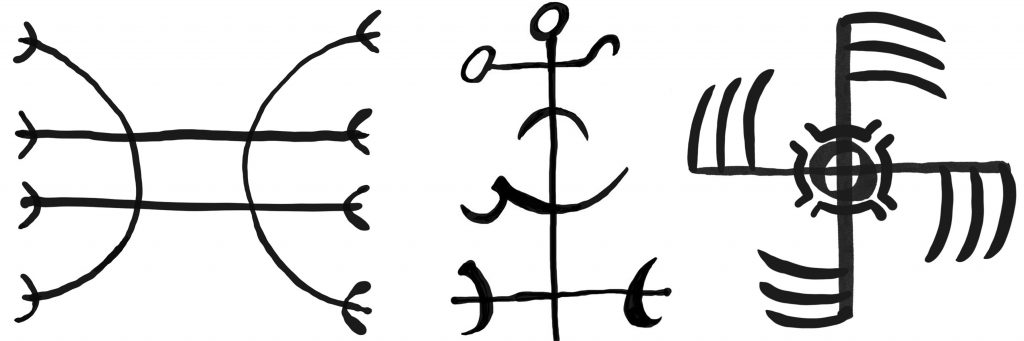

Icelandic magic staves shed light on what was so important in society that people sought assistance from the supernatural. Shown here are three of the Glíma magic staves.